Reaching Pricing Parity: Public EV fast charger vs. traditional fuel

The fact that EV charging is currently cheaper than filling up your traditional gas tank has set a precedent that public EV charging will always remain less expensive. This is certainly a good thing to support the adoption of EVs, but the high infrastructure costs and low session revenues of charging sites make a challenging business case for charge point operators (CPOs). It’s vital that we build a profitable market while setting a revised consumer expectation for the cost of a charging session.

With <1 percent of vehicles on the road being electric today, it’s an industry too immature to understand what pricing the market can bear. Until we see larger adoption rates, it’s unlikely the market will find the true EV charging price equilibrium on a cost-per-mile basis, but benchmarking against the cost of fueling an internal combustion engine (ICE) tank is a good place to start. Once we have mass adoption, corridor charging sites (essentially fuel stations for EVs) could reasonably charge something near what a consumer is used to paying at the current pump.

However, there are other costs to consider as well. For one, increased adoption will likely drive up utility rates due to the sizable grid infrastructure investment needed. CPOs and utilities will need to account for these costs, which will result in higher consumer-facing prices. Can we find a middle ground that supports further EV adoption while also providing a positive business case for companies investing in this vital infrastructure?

The new energy retailers

A colleague of mine recently referred to CPOs that own and operate EV charging stations as “energy retailers.” Utilities aren’t the only energy retailers; charging companies and even local fuel stations that installed chargers are technically retailing energy as well. With the responsibility to install, maintain and operate EV infrastructure, CPOs must add a sufficient margin on top of the local utility company’s commercial rates to support their investments.

Comparing cost-per-mile metrics

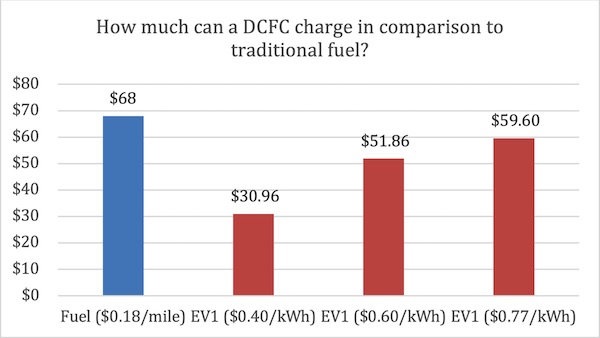

The EV charging price ceiling should logically be the equivalent of fueling an ICE, which can be considered by the cost per mile because miles are the only real comparable metric between vehicles. For example, an average ICE with a 22-mpg rating and 17-gallon fuel tank would be about $0.18 per mile to operate, assuming a fuel cost of about $4 per gallon. To look at an EV equivalent for $4 per gallon, let’s consider a Hyundai Ionic 6 with a 77.4-kWh battery and 325-mile range. To get the equivalent of $0.18 per mile, the CPO could retail energy at $0.77 per kilowatt-hour, assuming roughly 4.2 miles per kWh. That represents about a 90 percent premium on today’s average retail kilowatt-hour costs, and the maximum revenue a site can make per plug.

How much can CPOs reasonably charge?

The true value to a customer of providing fast and ultra-fast charging access is yet to be determined. Since the majority of charging will happen at the home and workplace, there’s no need to have the same national volume of DCFC plugs as we do fuel pumps. In fact, there will be a much lower attach rate — the ratio of cars on the road to plugs — versus that of traditional fuel pumps, which a recent NREL report estimated as 144:1 for EVs and 15:1 for fuel stations. With fewer EV chargers needed than gas pumps, wouldn’t basic supply and demand economics dictate a reason to charge a premium for these sites?

Like fuel prices, electricity costs shift quite drastically by market geography, not to mention the added complexity of time-of-use rates when there’s peak demand on the grid and electricity might be more expensive. Today, we see EV charging retail rates between $0.35 and $0.65 per kilowatt-hour, with the latter in areas like California and New York that also have higher fuel prices. Even on a conservative basis, there’s room to increase revenue per session from anywhere between 40 percent and 80 percent while still allowing for significant cost efficiencies over an ICE.

If I’m a CPO that retails for $0.40 per kilowatt-hour (about $0.095 per mile based on the previous scenario) I’d be 50 percent cheaper per mile than the gasoline alternative for the similar range. That begs the question of what would happen if I were only 25 percent cheaper than gasoline, thus increasing my retail price to $0.67 per kilowatt-hour. It’s a sizable percentage increase but also would represent a 68 percent increase to my annual revenues (assuming about 12 sessions per day), which adds $50,000 to my topline per port—not bad.

Finally, what if I went full tilt and was in parity with fuel at $0.77 per kilowatt-hour. A 180-kW DC fast charger supplying 36 kilowatt-hours, the average corridor charging session, would generate $27.72 of revenue leading to an increase of $13.32 per session. With no changes to site traffic, (i.e. still 12 sessions per day) I’d increase my annual topline revenue by 93 percent to $121,000, making significant increases in my IRR.

Most importantly, in parity with fuel, there’s a good chance that I’d be able to operate around a 50 percent margin, once taking into account the site’s fixed costs. According to a recent study, traditional fuel station owners make something like a 2 percent margin per gallon sold, so EV at scale makes for a very compelling argument given the potential spread in kWh prices once fixed infrastructure costs have been covered.

Consumers are price conscious and smart, so shifting perception in this very young industry as soon as possible is vital to set customer expectations and mindset for tomorrow. Increasing EV sales is reliant on having the infrastructure in the ground, but the market must incentivize site hosts to manage a competitive business in order to drive the needed adoption. The majority of traditional fuel stations are small businesses — ones without equity or debt funding opportunities, or institutional investments — so it’s vital the free-market system enable EV charging businesses to be profitable and yearn to invest in charging infrastructure. We should be starting to consider charging more at EV sites today because we’ll only just have to crank it up later.

Cole Rosson is Director of Business Development for Sparkion, an engineering-led provider of energy management solutions for the behind-the-meter industry with a focus on electric vehicle charging infrastructure (EVSE). Rosson has spent over a decade in the auto and e-mobility industries through roles at companies like Jaguar Land Rover, Ferrari, TikTok, and EVBox, where gained expertise in understanding the current and future market dynamics in the EV and EVSE spaces.

Cole Rosson is Director of Business Development for Sparkion, an engineering-led provider of energy management solutions for the behind-the-meter industry with a focus on electric vehicle charging infrastructure (EVSE). Rosson has spent over a decade in the auto and e-mobility industries through roles at companies like Jaguar Land Rover, Ferrari, TikTok, and EVBox, where gained expertise in understanding the current and future market dynamics in the EV and EVSE spaces.

Sparkion | sparkion.io

Author: Cole Rosson

Volume: 2024 January/February